The evidence of things not seen.

In the initial stages of the Pandemic, I remember reading an article about an elderly man in New York who was one of the first victims of COVID. The man was discovered deceased in his apartment after his neighbors had been concerned by his absence. A few neighbors reported that they had heard him coughing loudly at night.

The emphasis of the article was placed on the novel virus that was garnering headlines as it swept through the world with devastating consequences. But the article was still lodged in my memory several years after being published. There was something about the man's circumstances that haunted me. Yes, the man had (presumably) died of COVID. But wasn't it possible that he had died of another health scourge that had long been dormant but was just about to burst into the public consciousness?

What if the man had died from being socially isolated? What if he had actually died from loneliness?

The US Surgeon General's report on the Loneliness Pandemic was explosive when it landed in 2023. Over 82 dense pages of academic studies and research, its premise was glaringly clear: the lack of social connection poses a significant risk for individual health and longevity.

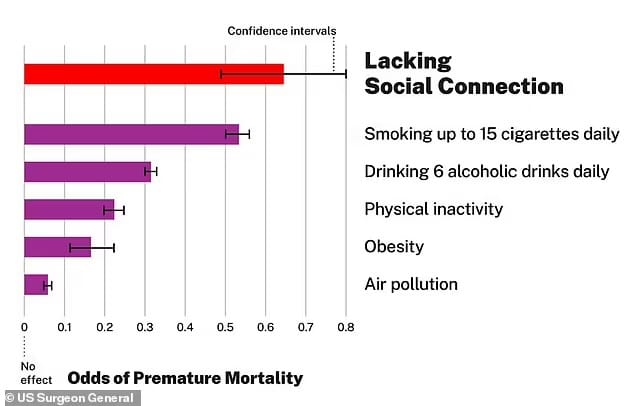

According to the report, loneliness (a subjective internal state) and social isolation (having few social relationships) increase the risk for premature death by 26% and 29% respectively. Among the revelatory findings was that being socially isolated had the same impact on health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day — a greater health risk than drinking six daily alcoholic beverages, physical inactivity, obesity, or air pollution.

The report is extremely discomforting because it asks us to challenge our preconceived notions. For example, can an ostensibly fit person (say a triathlete) actually be unhealthy by other metrics? According to the Surgeon General's report, if that person has very few friends or family members, the answer is yes.

According to the report, 61% of U.S. adults reported a lack of being "very connected" to other people. This makes loneliness a much more prevalent issue than smoking (12.5% of U.S. adults) diabetes (14.7%) and obesity (41.9%)

The numbers were even more stark in a study published in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine. According to that study, roughly 15-30% of people in the country experience loneliness as a "chronic" condition with profound health implications, including excessive BMI, higher blood pressure and cholesterol levels, elevated blood sugar, and decreased oxygen intake. All of these cardiovascular impairments translate into increased mortality risks. (1)

In a departure from the dry and sterile language that usually characterizes such studies, the authors were very eloquent in summarizing their study:

"The data suggests that a perceived sense of social connectedness serves as a scaffold for the self—damage the scaffold and the rest of the self begins to crumble.

"We have posited that loneliness is the social equivalent of physical pain, hunger, and thirst; the pain of social disconnection and the hunger and thirst for social connection motivate the maintenance and formation of social connections necessary for the survival of our genes." (2)

The authors of the study also noted that social isolation and loneliness are not exactly fertile grounds for healthy behavior. Very few people who experience a gnawing sense of estrangement from society opt to mitigate it by shooting hoops or kayaking.

“Loneliness leads to poor health behaviors, but only the impulsive kind, anything that could be damaging but that’s pleasurable,” co-author John Cacioppo said. “So higher fat and sugar in your diet. And alcoholism, drug addiction, and less exercise.” (3)

The theories espoused in the study referenced above were made more explicit when researchers at the University of Cambridge asked 40 people to fast for ten hours and, when finished, conducted brain scans while the participants gazed at pictures of appetizing food.

Immediately thereafter, the same participants were asked to spend ten hours alone without cell phones, email, or social contacts of any sort. After the ten hours had elapsed, there was a second brain scan, where participants looked at pictures of friends bonding with one another. The brain scans showed that hunger and isolation impacted the brain in a remarkably similar fashion. (4,5)

Loneliness also impacts the brain in much more profound ways. Dr Nancy Donovan, the director of the division of geriatric psychiatry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, conducted a study which found that the two primary antecedents of Alzheimers — the proteins amyloid and tau — are more present in people who score higher in loneliness tests.

“Even low levels of loneliness increase risk, and higher levels are associated with higher risk for dementia," said Dr. Donovan. (6)

It should come as no surprise that the Pandemic exacerbated these conditions, with people spending an average of almost two extra hours at home than they did twenty years ago, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Time Use Survey.

Of course, these are cold, bloodless statistics. What I really wanted to do was interview someone who had experienced social isolation and/or loneliness as a result of the Pandemic. Personal experience really humanizes a narrative, but my task was made much more difficult by the subject matter. Who wants to be profiled in an article about loneliness? The condition is still stigmatized, even given the vast number of people who suffer from it. According to the Surgeon General's report, less than 20 percent of people who experience loneliness view it as a problem.

But I knew the perfect candidate for an interview. I see his face every time I glance in a mirror.

Before I get too far into my personal narrative, I think it's important to acknowledge that I'm an introvert. Although introversion is often conflated with shyness, they're two distinct characteristics. I'm not shy at all. "Shyness" is a fear of social interactions, whereas "introversion" is a matter of where one derives their energy. Extroverts thrive in large social gatherings, while introverts generally prefer more intimate gatherings and having more time alone to "recharge."

Another important caveat — the world is oriented toward extroverts. For every time someone is complimented for being "the life of the party," there's no equivalent accolade for being the "champion of quiet contemplation." Introverts have a lot to offer, and their gifts go largely unheralded in an extrovert-skewed world.

And then came COVID-19.

There is no mitigating the death, breakdown of social mores, and the academic losses that COVID-19 precipitated. It's a matter of record and the ramifications of the Pandemic will be felt for years. But while all that misery was being sown, an odd thing was happening: introverts were finding that the world was orienting toward them. No more idle chit-chat at the office or obligatory company mixers. More time for contemplation. And for me, lots of time for my biggest passion: cycling. Solo cycling.

But a month of solo bike rides on car-free roads turned into two months, and then a year. And then two. Perhaps most importantly, the Pandemic affected my friendships. Many of my closest friends are my clients, and because I train them remotely two or three times a week, I thought my friendship bucket was full. I was wrong. I let too many friendships fade away during the Pandemic.

It became very clear that what I initially thought was an "Introvert's Paradise," was actually an "Introvert's Trap." By the time I finally noticed it, I was in too deep. The dilemma was crystallized when my partner gave me a geography lesson I won't soon forget.

Last year, one of my closest friends invited me on a cycling trip to the Southern Coast of France, where he had recently moved. He even offered to pay for the airline ticket. My initial reaction was to hem and haw and offer up a plethora of excuses.

My partner gave me a sideways glance and said that it wasn't even about getting out of the country. Or the state. Or even the city of Oakland.

"You need to get out of the house," she said. (I did end up going, and made memories that will last a lifetime.)

My story certainly isn't unique. Many, many people are going through something similar, yet lack the words to express it.

That missing language was the crux of a recent TedX talk by Dr. Juliane Holt-Lunstad, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. Dr. Holt-Lunstad's groundbreaking study on loneliness was cited by the Surgeon General when comparing the condition to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day.

"Let's be very clear," said Holt-Lunstad. "I'm not claiming that if you have close intimate relationships with friends and family that you can still smoke, quit exercising, or forgo life-saving treatments. But what I am arguing is that we need to take our social relationships seriously for our health.

"We can’t put good relationships in the drinking water and there’s currently no pills for us to take," she continued. "We just spent trillions in economic stimulus. How much will a social recession cost the government if we don’t prioritize human connection?"

Perhaps the change starts with one of the most mundane staples of American life: the doctor's visit. In addition to questions about diet, exercise, and lifestyle habits, the doctor could gently inquire about friendship circles and how to possibly improve them.

Or perhaps the change starts closer to home. It's a beautiful sunny day. I see my bike on the stand. Prepped up and ready to go. The hills are calling me. But this time, I won't answer them. I've got a friend on the other line, and a coffee date all lined up.

Sources:

(1) Louise C Hawkley and John T Cacioppo (October 2010) "Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms." Annals Behavioral Medicine

(2) Ibid

(3) Lydialyle Gibson (Nov-Dec 2010) "The nature of loneliness." University of Chicago Magazine

(4) Marta Zaraska (02/28/2023) "How Loneliness Reshapes the Brain." Quanta Magazine

(5) Ibid

(6) Dana G. Smith (05/09/2024) "Loneliness Can Change the Brain." New York Times

Reach out: joshua@joshuabrandtpt.com

If you liked this article....please pass it along!

Member discussion