The astronomer's folly: the twisted history of the BMI.

If there was a Fitness and Health Hall of Fame, Adolph Quetelet would surely be deserving of a plaque. Although he lacked the strength of Jack LaLane, or the aesthetics and acumen of Schwarzenegger, his contributions were much more influential.

And that's the problem.

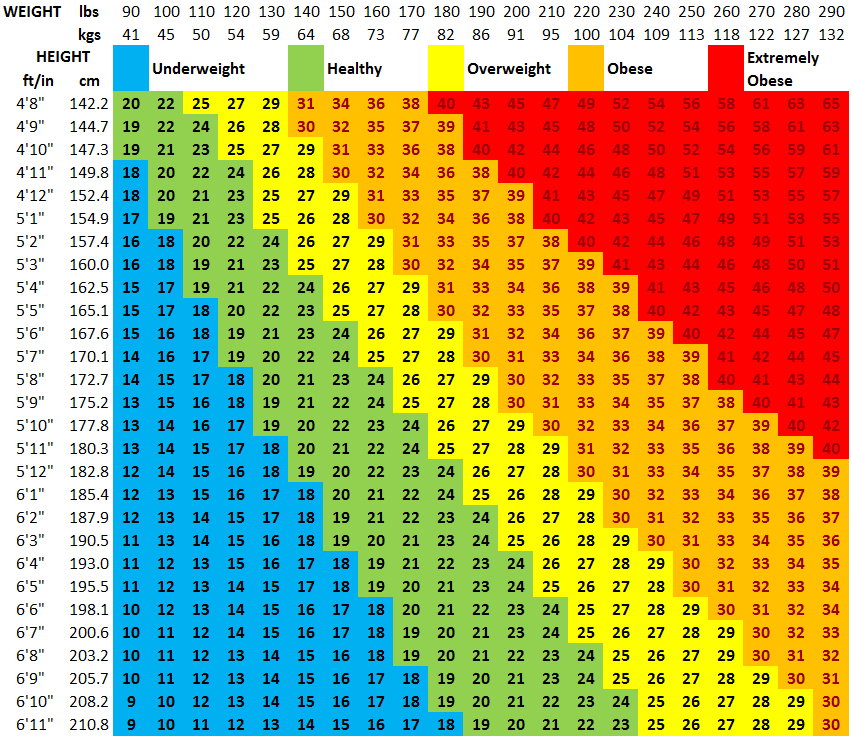

Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer and mathematician who died in 1874, is widely considered the “Father of the BMI,” which is the most widely used metric of health. The Body Mass Index is determined by diving someone’s weight (in kilograms) over the individual’s squared height in meters.

So, for example, the NBA star Anthony Edwards, at 6'4 and 225 lbs, would have a BMI of 27.5, classifying him as overweight. Take a glance at any photo of Edwards (above) and then correlate that with being overweight. That's totally absurd. The simplest take on the BMI as a metric of health is that it's "junk science." A more complex take is that it has perpetuated scientific discrimination and misclassified hundreds of thousands of people. It's just wrong on so many levels.

Quetelet was an odd choice to be the progenitor of such a widely used metric. He had no background in health or fitness. He was intrigued (some would say obsessed) with the idea of statistical norms. In the Atlantic, author Todd Rose posited that the Belgium Revolution of the 1830, which plunged the Netherlands into civil war (and eventually Belgium independence) was the big impetus for Quetelet's fondness for averages. Evidently, the astronomer wanted to impose order from chaos using statistics. (1)

The astronomer's first foray into statistical averages laid the groundwork for all his ensuing studies. He took the average chest measurement of over 5,000 Scottish soldiers and determined that it equated to 40 inches. This average was, to Quetelet, both the norm and aspirational — a number that was equated with beauty and perfection. Quetelet didn't stop there. He used statistical norms to calculate crime, poverty, marriage rates, and devised a system for measuring the height, weight, and other distinguishing characteristics of the average man ("l'homme moyen"). The system became known as the Quetelet Index — the precursor the BMI.

But it wasn't sufficient to have these numbers exist solely in the boring realm of statistics. Quetelet insisted that the numbers were imbued with a much larger social significance. "Everything differing from the Average Man's proportions and condition, would constitute deformity and disease," Quetelet said. “The Average Man represent(s) all that is great, good, or beautiful." (2) Among the luminaries that lauded his work were Florence Nightingale, Karl Marx, and Francis Galton, who used the QI as the basis for his racially charged scientific theories known as 'eugenics." (3)

The BMI was codified into the current lexicon in a 1972 article by Dr. Ancel Keys, who used the Quetelet Index as a foundation. Keys was most famous for his Minnesota Starvation Experiment (which tested deprivation of WW Two conscientious objectors) and the Seven Countries Study, which focused on diet and cardiovascular disease. One of the most profound shortcomings of Key's work is that (similar to Quetelet) it primarily studied white men of European ancestry. This is a fundamental structural error as different ethnic populations have different body types. For example, what might constitute obesity in an average Asian male would not necessarily constitute obesity in an average American male.

Keys also attached non-scientific interpretations to people who were overweight, calling obesity “disgusting as well as a hazard to health … ethically repugnant … and hard on clothes and furniture” (4) Interestingly, Keys also held that obesity "does not itself cause heart disease" and was not “necessarily dangerous for mortality risk in the average working man in the traditional populations we studied in mid century.” (5)

Those last quotes are telling, because it gets to the crux of the real deficiencies of the BMI: perceived health versus actual health. When Keys references the health of the "average working man" in 1950 the metrics are quite a bit different than those concerning the "average working man" in 2024. Many of the jobs of the 1950s were still physical and required movement. Not so in the 21st Century, where the average working man sits at a desk for eight hours. In simpler terms, the average working man in 1950 was going to be healthier because he moved more than the average working man in 2024, regardless of weight.

Let's take another example. Individual "A" is six feet tall and weighs 155 pounds. This places him squarely in the "normal" range. He also smokes and never exercises. He has very little muscle tone and functional strength. He gets winded walking up small hills. Individual "B" is six feet tall and weighs 200 pounds. The BMI has this person as "overweight." He exercises every day and never smokes. He has a lot of muscle, great strength, and enjoys long, arduous hikes. According to the BMI, individual "A" is the healthy one. This points to the most glaring structural error of the BMI: it doesn't take muscle into account. Muscle is denser than fat (meaning it weighs more). It's also imperative for living a healthy, active life, and people devoid of muscle density are not healthy, but that's the subject for another article. It's the same reason why Anthony Edwards is classified as "overweight" by the BMI — he has a LOT of muscle.

If any further convincing was needed as to the arbitrary nature of the BMI, when the National Institute of Health (NIH) decided to adopt the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for BMI in 1998, the cut-off point between being "normal" and "overweight" was lowered from a BMI of 27.8 (men) and 27.3 (women) to 25, thus reclassifying millions of people virtually overnight with the stroke of the keyboard. (6)

In a landmark 2016 study from UCLA, it was found that more than 30 percent of people with BMIs in the "normal" range (roughly 20 million people) are actually unhealthy based upon other metrics, while 2 million people considered "very obese" (a BMI of 35 or higher) are actually healthy based upon similar metrics — an anomaly that pertains to roughly 15 percent of the general U.S. population. (7)

So, the BMI provides a very cursory (albeit flawed) indicator of health.

But, as an adjunct, several quick fitness and health tests could also be administered. I think these would give a much more accurate indication of general fitness. They could include (a) a cardio test (such as "marching" with knees high for two minutes) (b) a strength test such as a push-up or modified push-up (using a lowered table) and (c) a balance test such as standing on one foot for a minute. These would expose the deficiencies in health and fitness more accurately than a BMI test.

In conclusion, it's best to take any BMI measurements with the proverbial grain of salt. Or, in a nod to the provenance of the BMI, have a nice piece of Belgium chocolate. Just be sure it's after a long walk. Hopefully with some good friends.

Joshua Brandt is an Oakland based personal trainer.

He can be reached at joshua@joshuabrandtpt.com or (415) 412-7339.

Initial consultation and session is free.

(1) Rose, Todd. (02/08/16) "How the Idea of the 'Normal' Person Got Invented." The Atlantic.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Jahoda, Gustav. (9/04/2015) "Quetelet and the Emergence of the Behavioral Sciences." PubMed Central

(4) Blackburn, Henry and Jacobs, David Jr. (06/2014) "Commentary: Origins and Evolution of Body Mass Index (BMI): Continuing Saga." International Journal of Epidemiology. Volume 43 (Issue 3) Pages 665-669

(5) Ibid.

(6) Nuttall, Frank Q. (05/2015) "Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review," Nutr Today. Volume 50 (Issue 3) Pages 117-128

(7) Tomiyama, A J, Hunger, J M, Wells, C. (02/04/2016) "Misclassification of Cardiometabolic Health When Using BMI categories in NHANES 2005-2012" International Journal of Obesity. Issue 40 Pages 883-886

Member discussion